For a Buddhist, beginning the journey along the road to enlightenment commences with the first understanding of the possibility of realising our Buddha nature. It is only when we fully understand this possibility of evolution into a higher being and discover the need to visualise our inner potential that we see the necessity for the development of an art form which matches our aspirations. In the religious arts of the world’s many and diverse cultures, few have provided as wide a canvas as the Tibetan on which to project visualisations of the vast range of possible aspects of the enlightened mind.

Origins

The Buddha’s task as a teacher could not even

begin until works of art had opened the people’s Tibetan Monk - yellow hat

sectimagination to the revelation of new perceptions. So we find that in the

Buddhist scriptures almost every discourse is preceded by some sort of miracle,

some dramatic revelation of an extraordinary perception to stimulate the

people’s imaginations. After the Buddha’s death those who knew him began to

make icons of his liberating presence, although at first it was considered that

no human representation could do justice to his memory, so that symbols such as

the wheel (of the Law), or the trees (of spiritual enlightenment) were used.

By the time Buddhism came to Tibet in the

seventh century AD, however, the artistic expression of the Mahayana, or

Universal Vehicle, had reached considerable heights of inspiration. Sakyamuni

Buddha, various cosmic Buddhas, magnificent female and male Bodhisattvas, all

were portrayed in splendid paradise-like settings. And with the development of

Tantric Buddhism the archetypal imagery went more deeply into the unconscious

mind to uncover other enlightening possibilities, both terrifying and benign.

The earliest surviving Tibetan images date

from the ninth century AD, and from that time until the present a wealth of

magnificent painting and sculpture survives which has served both as the focus

of meditation visualisations for many generations of Buddhist adepts, as well

as educational illustrations for ordinary Tibetan people. Tragically, since the

Chinese occupation began in 1949, many thousands of temples with their splendid

wall paintings and magnificent sculptures have been destroyed, so that today

there are probably many more beautiful Tibetan works of art in Western museums

and private collections than presently exist in Tibet.

Painting

Magnificent examples of Tibetan temple wall

paintings still exist, however, both in Tibet itself (Tsaparang, the Gyantse

Kumbum), in the Tibetan cultural areas of Indian Ladakh Alchi), and Himachal

Pradesh (Tabo), in Nepal (Mustang) and in Bhutan (Paro Dzong).

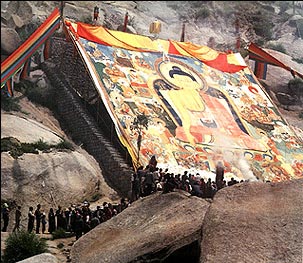

ThangkaHowever, the painting medium best

known outside Tibet is the thangka, or scroll painting. Usually painted on

cotton cloth, more rarely on silk, colours are traditionally made from minerals

as well as vegetable dyes. Before application they are de-saturated in varying

degrees in lime and mixed with boiled gum Arabic. These ‘stone’ colours

maintain their intensity so well that many old thangkas still retain striking

colours. Today, Tibetan artists also use modern synthetic dyes.

Thangkas are traditionally mounted in frames

of silk brocade with a pole or batten at the top and bottom so that it can be

easily hung. Since it is also easily rolled up, the thangka can be stored away

or readily transported from once place to another. Itinerant lamas used them as

icons of personal devotion and to sanctify tents in which they held teachings

of Buddhist doctrine. They are also used as effective teaching aids. In most

Tibetan homes the thangka, together with small bronze images, is an integral

part of the family altar and a vehicle of visual dharma.

Manuscripts also are often adorned with

miniature paintings, as are their wooden covers, and sets of initiation cards,

called tsakali, which are another medium of miniature painting.

Sculpture

Metal, clay, stucco, wood, stone, and butter

are all used in the creation of sculptural images, yet by far the best known of

these is metal, since small, portable, bronze images of a great variety of

meditation deities are most frequently encountered. Nevertheless, clay and

stucco have been used since ancient times, particularly in the creation of very

large images installed in monasteries and temples. Wood is also widely used,

intricately carved for entrances to temples and for interior pillars and in covers

for scriptures in monastery libraries. Most portable images, however, are made

from metal, usually bronze, but occasionally silver or gold. Bronzes are

usually made by the ‘lost wax process’, where a wax image is created, then

coated with a clay based mould which is subsequently baked allowing the wax to

melt and drain away, replacing it with molten metal. The finished image is

often then gilded and adorned with precious and semi precious stones. Metal

images are also sometimes made by the repousse method, where copper, or less

commonly silver or gold, is hammered out into the required shape from `the

reverse side. Works of art are usually commissioned, either by monasteries or

lay patrons, and their execution generally follows strict canonical rules as to

proportions, symbols and colours, in accordance with artistic manuals. Tibetan

art is largely anonymous, and this custom of artistic anonymity is grounded in

the Buddhist belief in working toward the elimination of the individual ego.

The Tibetan attitude to a work of art is that when it is successfully completed

it has an existence of its own and an inherent power to help the viewer come to

spiritual realisation. It ceases to be the property of the artist when it

leaves his studio.

Form and Function

The form given to a painted or sculpted image

follows a clear and well defined iconography set out in the appropriate texts,

whilst artists’ manuals illustrate the strict measures to be observed in

achieving correct proportion and balance. The Tibetan artist, like his Indian

counterpart, is not free to improvise on his personal concepts of the

appearance of an individual deity but is required to work within a well defined

structure. In the tantric art of Tibetan Buddhism, benign, wrathful, serene or

terrifying deities all illustrate an aspect of the Buddha mind, or the

potential to be found in each of us, so that the artist projects for us

archetypal images from deep within our subconscious, inviting us to contemplate

those aspects of our being which usually remain hidden. For the meditation

practitioner, such images are models for the process of visualisation, where

the adept develops the ability, through stabilised concentration and cultivated

inner vision, to visualise the deity in all its phenomenal detail and then

absorb this vision into him/herself and so absorb the spiritual qualities

particular to that deity.

Butter Sculptures

These are a complex and uniquely Tibetan

concept and are usually constructed by teams of monks for a festival or

religious event. They are not entirely made from butter, however, being

constructed on frames of wood and leather, to which are applied barley flour

and butter dough. They are then painted. Some were truly gigantic being as high

as a three storey building. After the ceremony they are destroyed. In this they

are like sand mandalas such as the well known Kalachakra Sand Mandala,

painstakingly constructed over many days from different coloured grains of sand

before being swept away at the end of the ceremony. The symbolism behind the

destruction of such works is based on the illusory nature of things, even those

we cherish most.

Decorative Arts and Crafts

Although Tibet had no political ties with

China after the end of the Yuan Dynasty (mid 14th century), there were

nevertheless frequent visits of monks and lamas to China from the great Tibetan

monasteries. This enhanced trade between the two countries and added greatly to

the monasteries’ wealth, at the same time providing a channel through which

cultural and artistic influences enriched Tibetan life.

Magnificent examples of Tibetan temple wall paintings still exist, however, both in Tibet itself (Tsaparang, the Gyantse Kumbum), in the Tibetan cultural areas of Indian Ladakh Alchi), and Himachal Pradesh (Tabo), in Nepal (Mustang) and in Bhutan (Paro Dzong).

Decorative Arts and Crafts

Although Tibet had no political ties with

China after the end of the Yuan Dynasty (mid 14th century), there

were nevertheless frequent visits of monks and lamas to China from the great

Tibetan monasteries. This enhanced trade between the two countries and added

greatly to the monasteries’ wealth, at the same time providing a channel

through which cultural and artistic influences enriched Tibetan life.

Silk

brocades and richly worked robes, pearls and precious stones, ritual vessels

and incense burners, gilt images and lacquered goods, all found their way into

the homes of the aristocracy and into the monasteries. Tibetans produced

earthenware, often of fine quality, but porcelain from China, especially since

the Ming period, was also highly prized.

The

Tibetan love of exuberant decoration resulted in everyday items being produced

with wonderful embellishments. Nearly every item used by Tibetans was fashioned

in this highly decorative way. Ink pots, tinder pouches, knives, teapots,

storage vessels, all were decorated lavishly in characteristic ways.

Tibetan

artisans are skillful people, and they have long produced large quantities of

ornate and intricate silver and gold jewellery, often set with coral, turquoise

and other precious stones. Carpet weaving for domestic and monastic use is

another ancient craft, and carpets are popular products from refugee

communities even today.

Tibetan

artisans are skillful people, and they have long produced large quantities of

ornate and intricate silver and gold jewellery, often set with coral, turquoise

and other precious stones. Carpet weaving for domestic and monastic use is

another ancient craft, and carpets are popular products from refugee

communities even today.

Carved

and painted wooden tables and cabinets are still in high demand as are silver

lined wooden bowls for butter tea. Crafts and decorative arts enormously

enriched Tibetan life and penetrated all levels of society.

The Arts in Exile

In

Dharamsala, the Centre for Tibetan Art and Crafts was established in 1977 under

the auspices of His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s Charitable Trust. Its primary

purpose is not only to preserve essential areas of the endangered Tibetan

culture but to inspire fresh enthusiasm and creativity in Tibetan artistic

expression.

Selection

of students is made on the basis of both aptitude and economic background with

priority given to those applicants who are particularly needy. Most of the

crafts produced are exported through the offices of the Charitable Trust.

The

Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA) was established in Dharamsala in

1971 as a repository for ancient cultural objects, books and manuscripts from

Tibet. LTWA now has eight departments: Research and Translation, Publications,

Oral History and Film Documentation, Reference (reading room), Tibetan Studies,

Tibetan manuscripts, Museum, School for Thangka Painting and Wood Carving. LTWA

has a team of Tibetan scholars engaged in research, translation, instruction

and the publication of books.

Since

its founding the Library has acquired a reputation as an international centre

for Tibetan Studies. To date, more than five thousand scholars and research

students from all over the world have benefited from this unique educational

institution. LTWA also offers regular classes in Buddhist philosophy.

[ Text with kind permission from the Australian Tibetan Society Inc. ]

No comments :

Post a Comment