In the Vitakkasaṇṭhāna Sutta [Majjhima Nikāya 20], the Buddha concisely outlines a discipline for the more conscious management of our thinking. Even experienced practitioners of vipassanā who are schooled in the techniques of non-judgmental awareness may be surprised to learn of this teaching of the Buddha. For this discourse encourages the yogi who would attain “the higher mind” not merely to observe thoughts dispassionately but to exercise deliberate thought maintenance. By following the regimen outlined in the Vitakkasaṇṭhāna Sutta, we are able to influence our thinking patterns and gradually cultivate minds that have a greater tendency to generate thoughts more appropriate to wisdom and liberation. It is not necessary for us to be buffeted about by our own minds.

Like all phenomena, the mind is a conditioned reality. Its existence is interdependent with other factors. Although thoughts may seem to come out of the blue, other mental and physical processes prepare for their arising. Following karmic principle, wholesome thoughts create the propensity for more wholesome thoughts; unwholesome thoughts set the stage for unwholesome thoughts. In this sense, at least, we are responsible for what we think. While we may not be in conscious control of each and every thought, we can choose which thoughts to entertain and develop and which to disregard and release. Cultivating a discipline for the selection and fostering of thoughts increases our capacities to care for our thoughts with wisdom. The Vitakkasaṇṭhāna Sutta provides five very practical techniques for such a discipline. In this sutta, the Buddha speaks specifically about one feature of the care for the mind: the relaxation of unwholesome thoughts.

It requires skill to recognize unskillful thoughts.

Yet before we are able to relax unwholesome thoughts, they must be recognized as such. One characteristic of the unskilled mind, of course, is its inability clearly to distinguish between wholesome and unwholesome thoughts. Just as the unskilled mind has difficulty even knowing when it is absorbed in thought, it finds it hard to know when a thought is edifying or corrosive—or even the importance of this distinction. An apocryphal anecdote from the life of Sigmund Freud puts this difficulty in an amusing light. Freud supposedly asked one his patients if she were ever troubled by lustful thoughts. “No,” she replied, “I rather enjoy them.”

In the Vitakkasaṇṭhāna Sutta, the Buddha identifies the qualities of an unwholesome thought and explains its problematic nature. An unwholesome thought is akusala, “unskillful.” Put simply, it is a thought that is not conducive to liberation but rather promotes suffering. Unwholesome thoughts may be recognized by certain telltale traits. Specifically, they are connected to desire, hatred, or delusion. Thoughts associated with desire are predicated on pleasant experiences and our voracious appetite for pleasure. Thoughts of hatred arise out of aversion and our desire to avoid unpleasant experiences. Deluded thoughts are thoughts that are at odds with reality and result from our failure to see ourselves and the world as they really are. It requires skill, of course, to recognize unskillful thoughts, and the development of this skill requires practice and vigilance. Given time and diligence, we begin to realize when our thoughts are associated with desire, aversion, and delusion. Once they have been recognized, they can be disempowered.

The Buddha’s five techniques for relaxing unwholesome thoughts proceeds in a step-by-step manner. He begins with the simplest and easiest procedure. In the event that technique fails, he advises a second step; if that does not work, he offers a third, then a fourth, and finally the fifth. These methods proceed from those requiring the least amount of psychic energy to that those requiring the most.

Bhikkhus, when a bhikkhu is pursuing the higher mind, from time to time he should give attention to five signs.

What are the five?

Here, when a bhikkhu is giving attention to some sign, and owing to that sign there arise in him evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion, then he should…give attention to some other sign connected with what is wholesome.

…Just as a skilled carpenter or his apprentice might knock out, remove, and extract a course peg by means of a fine one, so too…when he gives attention to some other sign connected with what is wholesome, then any evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion are abandoned in him and subside. With the abandoning of them his mind becomes steadied internally, quieted, brought to singleness, and concentrated.

Replacement

Perhaps the easiest means for ridding ourselves of problematic thoughts, once they have been identified, is replacement. Just as woodworker might knock out a coarse peg with a fine one, says the Buddha, so should we supplant the unwholesome thought with a wholesome one. The most effective approach is to match the unskillful thought with an appropriate skillful one. Thoughts of desire, then, can be substituted by thoughts of the impermanence of the object of desire. Thoughts of hatred are replaced with notions of friendliness and compassion. Deluded thoughts are overcome by an acceptance of reality. Initially, the technique of replacement may seem awkward and artificial. It may appear, as the metaphor suggests, rather wooden. With practice, however, it becomes habitual, thus needing only the slightest expenditure of mental energy.

If, while he is giving attention to some other sign connected with what is wholesome, there still arise in him evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion, then he should examine the danger in those thoughts thus: “These thoughts are unwholesome, they are reprehensible, they result in suffering.”

…Just as a man or a woman, young, youthful, and fond of ornaments, would be horrified, humiliated, and disgusted if the carcass of a snake or a dog or a human being were hung around his or her neck, so too…when he examines the danger in those thoughts thus: “These thoughts are unwholesome, they are reprehensible, they result in suffering,” then any evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion are abandoned in him and subside. With the abandoning of them his mind becomes steadied internally, quieted, brought to singleness, and concentrated.

Reflection on Results

If, while he is examining the danger in those thoughts, there still arise in him evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion, then he should try to forget those thoughts and should not give attention to them. If replacing unskillful thoughts with skillful thoughts proves unsuccessful, the Buddha recommends that we contemplate the consequences of the unwholesome thought. We might ponder the effects of holding this unwise notion. It helps me to consider the kind of person I become when I entertain and foster a particular unwholesome thought. If, as the first verse of the Dhammapada has it, mind shapes reality, that as we think so we become, then our thoughts have ineluctable consequences, not unlike the way high caloric foods have consequences for our physical health. Just as I might reflect on my clogged arteries as I contemplate eating a slice of cheesecake—as pleasurable as it might be—so I follow the trajectory of an unwholesome thought. I envision where a diet of such thoughts might lead. Do I really want to become the kind of person whose life has been shaped by thoughts of greed and hatred? In the Vitakkasaṇṭhāna Sutta, the Buddha likens the yogi’s unwholesome thought to a snake or animal carcass around the neck of a well-dressed person. Such a thought is unbecoming to a wise and compassionate person.

If, while he is examining the danger in those thoughts, there still arise in him evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion, then he should try to forget those thoughts and should not give attention to them.

…Just as a man with good eyes who did not want to see forms that had come within range of sight would either shut his eyes or look away, so too…when he tries to forget those thoughts and does not give attention to them, then any evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion are abandoned in him and subside. With the abandoning of them his mind becomes steadied internally, quieted, brought to singleness, and concentrated.

Redirecting

If the previous techniques are unable to relax the troubling thought, the Buddha encourages redirecting attention away from the thought to something more wholesome. To clarify this technique, the Buddha uses the metaphor of averting one’s gaze to avoid seeing certain objects. This method, of course, is familiar to meditators. When the mind has been distracted by thought, we simply return attention back to the breath. Once again, the practice of meditation strengthens our ability to employ this technique. Redirecting attention relies on the fundamental impermanence of reality to achieve success. If we can simply divert attention to more wholesome objects, the distracting thought, given its impermanent nature, will dissolve of its own accord. All things that arise must fall.

That wonderful but almost extinct Christian community, the Shakers, has an old expression that nicely reflects the wisdom of redirecting attention. “Hands to work,” they say, “and hearts to God.” This Shaker admonishment recognizes the importance of continually redirecting attention to wholesome activity and thoughts. The undisciplined attention becomes the workshop of the devil. Far better to keep one’s self diligently occupied with wholesome activity lest the straying mind comes to dwell in greed, aversion, and delusion.

If, while he is trying to forget those thoughts and is not giving attention to them, there still arise in him evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion, then he should give attention to stilling the thought-formation of those thoughts.

…Just as a man walking fast might consider: “Why am I walking fast? What if I walk slowly?” and he would walk slowly; then he might consider: “Why am I walking slowly? What if I stand?” and he would stand; then he might consider: “Why am I standing? What if I sit?” and he would sit; then he might consider: “Why am I sitting? What if I lie down?” and he would lie down. By doing so he would substitute for each grosser posture one that was subtler. So too…when he gives attention to stilling the thought-formation of those thoughts, then any evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion are abandoned in him and subside. With the abandoning of them his mind becomes steadied internally, quieted, brought to singleness, and concentrated.

Reconstructing

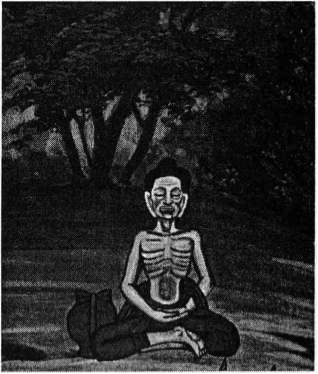

We might call the Buddha’s fourth technique reconstructing, which is analyzing the formation of the unskillful thought. In the second method, reflecting on results, we pursue the forward trajectory of such a thought. With reconstructing, we move in the other direction, examining the antecedents that have given rise to an unwholesome notion in the first place. Since the mind is a conditioned phenomenon, these distracting thoughts are predicated on other thoughts. It is possible, then, carefully to explore the roots of unskillful thinking. If I am having unkind thoughts toward another, for instance, I am often able to see that those thoughts emerge out of a feeling of envy. Pursuing this insight further, I notice that my envy derives from a sense of personal inadequacy, which in turn rests on the belief that this “I” is a substantial entity, separate from the rest of reality. By systematically reconstructing the formation of an unwholesome thought, one is able to return it to its antecedent causes to see how it is rooted in a false apprehension of reality. Such a process is often effective in rendering the thought totally harmless.

If, while he is giving attention to stilling the thought-formation of those thoughts, there still arise in him evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion, then, with his teeth clenched and his tongue pressed against the roof of his mouth, he beats down, constrains, and crushes mind with mind.

…Just as a strong man might seize a weaker man by the head or shoulders and beat him down, constrain him, and crush him, so too…when, with his teeth clenched and his tongue pressed against the roof of his mouth, he beats down, constrains, and crushes mind with mind, then any evil unwholesome thoughts connected with desire, with hate, and with delusion are abandoned in him and subside. With the abandoning of them his mind becomes steadied internally, quieted, brought to singleness, and concentrated.

Resistance

The most radical technique for removing distracting thoughts is resisting the “evil mind” by means of the “good mind.” As a final resort, the Buddha advises the yogi to clench her teeth and press her tongue against the roof of her mouth as she “beats down, constrains, and crushes mind with mind.” The Buddha compares this method to the way a stronger man might subdue and control a weaker one, literally seizing him by the head and shoulders. This analogy seems uncharacteristically brutal for the Buddha’s teaching, and it might appear a rather inappropriate metaphor for “relaxing” thinking patterns. But the intensity of the analogy is instructive if taken in the proper spirit. Its radical nature is consistent with a similar saying of Jesus. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus admonishes his students: If your right eye causes you to sin, tear it out and throw it away; it is better for you to lose one of your members than for your whole body to be thrown into hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away (Matt. 5:29- 30a).

In these teachings, the Buddha and Jesus alike emphasize the seriousness of evil actions, whether those are the actions of the hand or eye or the actions of the mind. What may now seem small and insignificant over time determines who we become. The tyranny of unwholesome thoughts over our lives needs to be ended, even if we must finally resort to clenching our teeth and crushing the mind with mind. Our liberation depends upon it.

Thinking Responsibly

We may not be able to control particular thoughts, but we can influence the conditioned mind that gives rise to particular thoughts. We can prepare a fertile mental soil that increases the likelihood of germinating wholesome, skillful ideas and decreases the likelihood of growing distracting ones. But such mind must be tended with a watchful eye. A seasoned gardener once gave me this simple advice: “When you see a weed, pluck it.” In other words, it’s in the nature of weeds to grow fast and wild; don’t wait until the garden is overrun with unwanted foliage before you try to remedy the situation. Unwholesome thoughts are the same. They grow fast and wild and leech vital nutrients from the thoughts that conduce to our liberation. We ignore them at our peril.

Mark Muesse is associate professor of Religious Studies at Rhodes College in Memphis. He received his doctorate from Harvard University, and has studied at the International Buddhist Meditation Center, Wat Mahadhatu, Bangkok. All quotations are from: Vitakkasaṇṭhāna Sutta in The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha: A New Translation of the Majjhima Nikāya. Trans., Bhikkhu Nanamoli and Ed., Bhikkhu Bodhi. Boston:Wisdom Publications, 1995.

No comments :

Post a Comment